In 1689, London bookseller Jacob Tonson published an anonymous skit in Latin entitled AUCTIO DAVISIANA Oxonii habita. Per Gulielmum Cooper, Edvar. Millingtonum, Bibliop. Lond.[i] This fake auction catalogue was in fact a playlet of fourteen pages, staging six characters: C and W were auctioneers with K, B, S and D being purchasers at the sale.

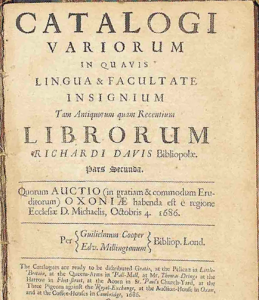

The play satirised the real auction of a stock of 40,000 volumes previously owned by Oxford bookseller Richard Davis, whose bankruptcy was parodied by the anonymous author as “a memorable matter indeed, worthy of the tragic buskin of Sophocles”. Between 1686 and 1692, London auctioneering pioneers William Cooper (W) and his sometimes partner Edward Millington (C) organised four sales in Oxford to dispose of the books.

Auctio Davisiana gives a very biased yet ultimately unique perspective on these two characters, the conduct of a late seventeenth-century auction, as well as the type and state of books for sale.

“Who of you will represent the person of Millington, and also afterwards that of Cooper?”

The author was quickly identified as George Smalridge (1662-1719), future Bishop of Bristol.[ii] He was then a tutor at Christ Church in Oxford and a protégé of famed antiquarian Ashmole. A 1791 reprint of the text in the Musae Anglicanae gave away the identity of the actors, all students of Smalridge.[iii]

Portrait of Smalridge (Wikimedia)

The poet’s verses were not merciful to the booksellers. First described as a “man of such wonderful and notable gravity”, Cooper was quickly derided for his “monstruous paunch” and “admirable breadth of visage”; Millington did not fare better with his “Stentor’s lungs, consummate impudence – a very wind-bag whose hollow bellows blow lies” always on the verge of losing his mind. The “Great” Cooper was a “liar”, Millington a pedantic imbecile.

“Come on then, and let us duly sing in alternate strains what is the manner of selling, what laws and regulations the auction observes, how the purchasers are arranged, what is the place, and any other incidents which can be fitly rendered in verse.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of this play is the description of the auction itself, its shady location, unsavoury crowd, and strange practices. At the time of publication, it had only been thirteen years since Cooper introduced auctioning in Great Britain with the sale of Lazarus Seaman’s library in 1676. In fact, Smalridge took several jabs at London and Oxford’s rival university town Cambridge, which successfully adopted the modern and revolting practice.

The sale took place in Northgate, as the “ignorant crowd calls it”, or Bocardo, as “style[d]” by scholars. “Dance gives place to bookseller”, remarked Smalridge in a striking opposition between the dignity of intellectual pursuits and the ignominy of this debauched neighbourhood. The antiquarian Anthony a Wood simply described the location of Davis’s auction as a stone factory.

The procession of purchasers and gawkers is likewise described in an unflattering manner: Smalridge despised the democratic sitting arrangement, allowing “the very scum of the mob” to sit elbow to elbow with Oxford’s elite.

Precious information is given about the conduct of the sale. Some, like its timeline, can be confirmed by paratextual elements in printed catalogues. Of the day itself, we learn that the conditions of sale are read aloud once the sale begins. Smalridge’s version is, of course, perverted. “If any dispute arises, it rests with you to decide it”, states Cooper’s scenic persona, washing his hands of any responsibilities. We are also given to hear the arguing of bidders, the poking and prompting of auctioneers, the tension rising with the size of the bids, and the gavel finally hitting the desk to end it all before a new lot item is put up for sale.

The play is punchy, witty, and often hilarious; but is it really a fair representation of auctions in the late seventeenth century? In Smalridge’s cruelty, it is almost impossible not to discern the fearful depiction of a struggle between a declining yet noble humanist tradition, the growing mercantile interests of booksellers, and the budding social aspirations of the middling sorts.

As for the quality of the books for sale, that is a story for another day!

[i] I am using the 1886 translation of the play published in Book-lore. The first part appeared in Volume III (pp.166-179) and the second in Volume IV (pp.1-9).

[ii] For more information about the author, see the Oxford dictionary of national biography: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1004640?rskey=LhoxGS&result=1

[iii] Codrington played the role of Millington and Woodward that of William Cooper. A plantation owner from the Barbados, soldier and renowned book collector, Codrington was recently in the news as Oxford students militate to rename the All Soul’s library bearing his name after he bequeathed the college with his private collection( https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/NEWS/11042474.The_shameful_truth_of_how_slavery_paid_for_fine_library/ ); for more information about Woodward, see: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/knight-william-1667-1721.

The purchasers in the auction were played by Arthur Kaye (probably https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/kaye-sir-arthur-1670-1726), Waller Bacon (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1715-1754/member/bacon-waller-1669-1734), Edward Stradling (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1715-1754/member/stradling-sir-edward-1672-1735) and George Dixon.