The catalogue of the books of the deceased “Mr Briot” that appeared in Paris in 1679, is a relatively early French sale catalogue. Unlike in the Dutch Republic, where the publishing of catalogues of private libraries offered for sale was standard procedure since the end of the 16th century (almost 1500 known editions for the 17th century alone!), this practice developed slowly in France and didn’t establish itself firmly until the 1720s. The number of (sale) catalogues of private collections printed in France during the “Grand Siècle” is subsequently low: I found traces of no more than 60 of them for the period 1632-1700.

The art of informing potential buyers

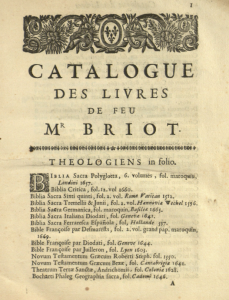

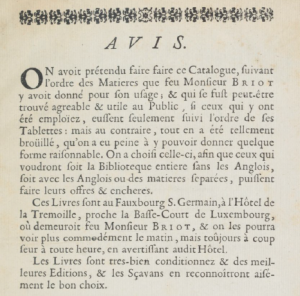

Some features of the Briot catalogue show that this kind of publication took some time to evolve into the standardized and commercially sophisticated “genre” we generally associate with early modern French book (sale) catalogues. For one thing, there is no mention of a publisher, printer or distributor. Only the place and the year of publication are indicated. One also searches in vain for specific information concerning the sale: dates, address, name of the person responsible etc.. In fact, you have to read the “avis” on the second folio to know at all that the collection is for sale:

[….] We have chosen this [order of presentation], so that those who want either the entire library, with or without the English [books], or separate subjects, will be able to make their offers & bids. These books are in the Faubourg S, Germain, in the house of La Trémoille [….] where the late Mister Briot resided; & one can see them most easily in the morning, but certainly at any hour after making an appointment at the house. [….]

Catalogue des livres de feu Mr. Briot (Copy 2, see below)

All this doesn’t seem like a very effective sales approach.

Uncertainty about the sales conditions indeed led none other than John Locke to miss out on this opportunity. In a letter to his friend Nicolas Toinard, dated 13-10-1679, he expresses his annoyance about the fact that he had been told that the library would be sold as a whole: if he had known he could buy individual items, he would certainly have bought some of Briot’s books.

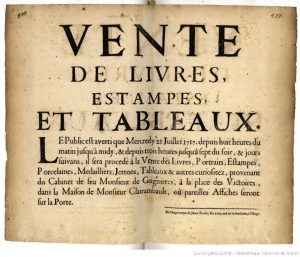

Normally book sale organisers put up posters in the streets indicating further details on the sale, but interested buyers from outside town necessarily had to rely on others to access this information in a timely way.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Clairambault 1032, f. 288-289

Publishing a catalogue: DIY?

One of the intriguing “behind-the-scene” questions concerning early modern private library (sale) catalogues regards the production and distribution process. How did this work in 17th-century France? What roles, responsibilities and regulations were involved? And, no less importantly, who was paying for what?

Although several contemporary documents allow us to catch a glimpse of these practicalites, it is difficult to get a clear and coherent idea of what the production process might have been like. For instance, while the prefaces of some catalogues state that the – mostly unidentified – compilers followed the order of books presented in the probate inventory, others explain that they have chosen a particular thematical order. I have been able to verify that the arrangement in the manuscript inventory of Briot’s books that was drawn up after his death in December 1678, is indeed different from the one adopted for the printed catalogue, but I have found no clues for identifying its compiler(s) and/or editor. The information gathered thus far seems to indicate that Briot’s catalogue was published at the expense of his heirs. It was probably Jacques de Rozemont, the guardian of Briot’s children, who ordered it. There is also evidence that he distributed it himself – for free?- among his contacts.

The surviving copies I have seen represent two different states of the catalogue. The relatively minor variants concern the title page, the place of the “avis”, and pp. 1-4. It is possible that the fact that in one of the versions, the “avis” very unpractically ended up as the last page of the catalogue, led to a decision to reset the first pages.

The printer

In an attempt to identify the printer of Briot’s catalogue by looking at the typographical ornaments that were used, I searched some specialised databases, such as BaTyR (http://www.bvh.univ-tours.fr/batyr/beta/en_index.php) and Fleuron (https://fleuron.lib.cam.ac.uk/). When this didn’t bring anything, I engaged in a study of the ornaments used in 17th century Parisian books available on the Internet. This quest finally paid off: the woodblocks used for the catalogue match the material of the printer and book seller Louis Billaine.

Catalogue des livres de feu Mr. Briot (Copy 1, see below)

L’Ambassade de D. Garcias de Silva Figueroa en Perse […] Paris, L. Billaine, 1667 (Lyon, B.M., 345590, on Google Books)

On the left: Histoire des trois derniers empereurs des Turcs. Depuis 1623 […], Vol. 1, Paris, Veuve L. Billaine, 1682. (National Library of the Czech Republic, on Google Books)

On the right: Catalogue des livres de feu Mr. Briot (Copy 1, see below)

Billaine’s name also surfaces in the account of the sale itself. It was conducted under the responsibility of the above mentioned Rozemont and it attracted around 140 different buyers, but that is for another blogpost, or two…

Copy 1

Catalogue des livres de feu Mr. Briot

Paris, s.n., 1679.

Augsburg, Universitätsbibliothek, 02/I.1.4.137

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:384-uba003721-4

Copy 2

Catalogue des livres de feu Mr. Briot

Paris, s.n., 1679.

Paris, BnF, Q.1960

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6311533m