The printed catalogues of private libraries we work with in the MEDIATE project not only constitute a rich source for researchers in the fields of literary studies and the history of ideas. They also provide valuable material for those interested in the economic history of the book in early modern Europe. The majority of our catalogues was published in the context of a sale or public auction. And catalogues that had been drawn up for other purposes were sometimes also used as sale catalogues. Many of them bear printed and handwritten information on sale conditions, estimated market values and book prices.

The price information we can gather from printed private library catalogues concerns the books listed in the catalogues as well as the catalogues themselves. In the early modern period, private library and other book trade catalogues were sometimes distributed for free. It was however not uncommon for publishers and book sellers to literally put a price on them.

Copies: Lyons, B.M., 491002 (Google Books) and Lyons, B.M., 371371 – T. 04 (2) (Numelyo)

In this context we can observe some interesting differences between practices in France, the Dutch Republic and the British Isles.

From the 1750s on, title pages of Dutch sale catalogues started to indicate that in order to get a copy, one had to donate a few “stuivers” for the poor. The amount asked for varied slightly, but it was most often set at two “stuivers”.

18th-century Dutch “stuivers”, source: Memory of the Netherlands

A non-exhaustive search in Book Sales Catalogues Online returned around 225 catalogues (a few of them retail or wholesale catalogues), mentioning this condition in Dutch and/or French. They all date from the period 1758-1800.

Copy: The Hague, K.B. (Google Books)

Was the sudden appearance of this stipulation due to new regulations?

When it came to dealing with the problem of poverty, city councils and other institutions in the Dutch Republic were always short of money, and they sometimes deployed creative ways of raising money for the poor.

For instance, in many public buildings and even on the work floor, one could find the so-called “armenbusjes”, charity boxes. Their filling didn’t only depend on the goodness of the hearts of those who passed by, but it also thrived on the practice of demanding a donation to the poor as a penalty for misconduct or breaking rules. According to a 1781 instruction for captains at sea, swearing boatsmen were to receive corporal punishment as well as being required to donate two “stuivers” to the poor.

Several local and provincial governments made use of the popularity of book auctions by taxing them. Maybe the idea of selling the printed catalogues on behalf of the poor was just another way of making the book trade contribute to a public cause. I’ve found no evidence that the revenues were destined for specific groups, such as members of the guild. Only the catalogue of the collection of the marquis de Saint-Simon further circumscribes “the poor” as “les pauvres de la religion réformée”.

In any case, this special provision made for Dutch auction catalogues seems to reflect a way of thinking about the status and commercial use of (auction) catalogues that differs from what we find elsewhere.

According to the information in British catalogues, prices paid for these booklists didn’t benefit the poor, but it was the purchaser himself who could profit: a number of catalogues indicate that if the buyer made a purchase at the sale, the price of the catalogue would be reimbursed.

At present, my inventory of French printed private library catalogues contains only one catalogue indicating that it was distributed at the price of “un décime pour les pauvres”. The rest of those that have prices on the title-page often specify if this is for a bound volume or a paperback, and in a few cases, they mention two different prices: it was cheaper to buy the catalogue before the start of the sale.

What can we conclude from this? One could be tempted to see in this difference yet another confirmation of the highly commercial character of British auction catalogues, of the pride that the French took in issuing quality publications, and maybe of the typical Dutch combination of mercantilism and Calvinism.

Anonymous, Caricature of the English bibliographer Isaac Gosset (1745-1812)

However, advertisements and catalogues published in the Catholic Southern Low Countries during the second half of the 18th century show that this region also knew the practice of connecting the sale of printed private library catalogues to poor relief. So maybe we should look at region rather than religion. It’s interesting to see that my sole French catalogue with a price on it that refers to “the pauvres” comes from Lille, a frontier city that only became French in 1668.

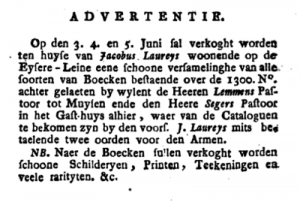

Wekelycks Bericht Voor de Stad en de Provincie Van Mechelen 02-06-1776

The catalogue of the deceased sir Lemmens is available from J. Laureys at the price of two “oorden” (half a stuiver)

To end on a bit of a sceptical note: one might wonder if the charity money raised from the selling of auction catalogues always reached its destination. Archival sources testify indeed to the fact that in the 18th century Dutch Republic, some of those in charge of the money for the poor couldn’t resist temptation.

Some things never change…

Anonymous, The Poor House of the Diaconate of the Reformed Church in The Hague, c. 1735

* With thanks to Rindert Jagersma and Juliette Reboul for providing information, and to Alicia Montoya for her comments on an earlier draft.